Readings on Nutrition

The process of nutritional evaluation in the United States

Eva Politzer Shronts, MSc, RD, CNSD.1

University of Minnesota

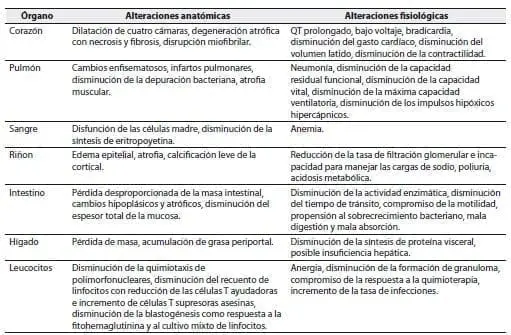

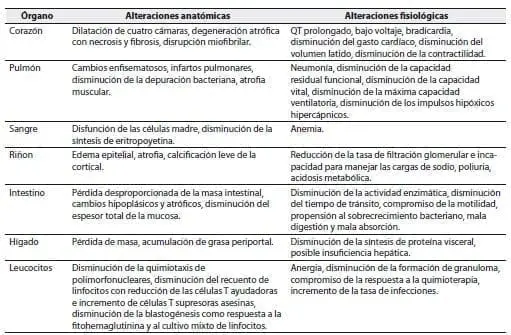

Alterations in nutritional status may occur as a consequence of an inadequate supply of substrates (for example: malnutrition) or as a consequence of an alteration in the metabolism of substrates (for example: sepsis). In either case, a reduction in lean body mass with subsequent loss of structure or function results (Table 1).

Table 1. Response of target organs in malnutrition.

Taken from Shronts EP, Cerra FB. The rational use of applied nutrition in the surgical in the setting.

In Paparella M, et al (Eds.). Otolaryngology. W. B. Saunders 1990. p. 658.

In both cases the goal is to prevent malnutrition from becoming an important cofactor in organ dysfunction and morbidity and mortality. This is achieved by providing or replacing nutrients in the case of malnutrition and supporting the alterations present in nutrient metabolism by adjusting the quantity and quality of the substrates in cases of hypermetabolism.

Whatever the underlying cause of malnutrition, the first step in providing adequate nutritional or metabolic support to a given patient is a complete US Nutrition Assessment. The evaluation of nutritional status is a dynamic process that begins with an initial baseline evaluation that must be maintained continuously throughout the patient’s treatment. The extent and frequency of subsequent Assessments may vary according to the physician’s individual and clinical judgment.

The nutritional assessment includes the following components: Clinical evaluation, evaluation of the somatic and visceral protein compartments, evaluation of nitrogen homeostasis and immunocompetence, evaluation of metabolic markers and vitamin and mineral deficiency, and determination of nutritional requirements.

Clinical evaluation

The clinical evaluation consists of a medical history, a dietary history, and a physical examination.

Medical record

The medical history should focus on the assessment of recent changes in body weight including the presence of edema and ascites; unintentional absolute weight loss, changes in appetite, especially alterations in taste, anorexia, nausea and vomiting, presence of diarrhea or steatorrhea and symptoms such as muscle cramps in the extremities. Of special interest are medications that may contribute to the development of the symptoms noted.(2-4)

Dietary history

A complete dietary history should include assessment of usual daily intake of calories, protein, sodium, and fluids. Any additional information, such as food preferences, meal frequency, food intolerance, and use of vitamin and mineral supplements, is also useful as it facilitates the identification of possible nutritional deficiencies and serves as a guide for planning. meals.(2-5)

(Read Also: Somatic Protein Compartment and Body Fat Stores)

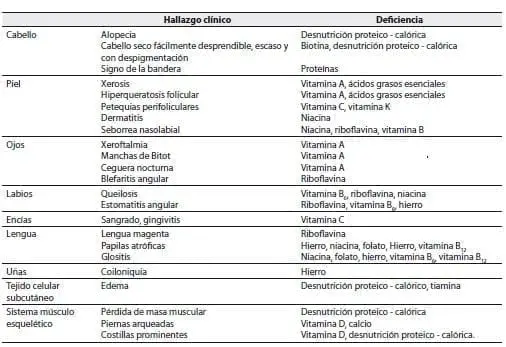

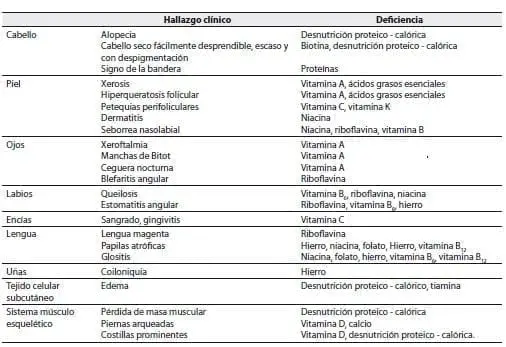

Physical exam

The physical examination is one of the oldest and most precise tools for nutritional assessment. Physical signs of protein-calorie malnutrition include the following: Obvious loss of body mass and subcutaneous fat; easily removable dry hair; dry, peeling skin; stomatitis, cheilosis and glossitis and neuromuscular irritability or neuropathy of the extremities (table 2).(2-4)

Table 2. Clinical findings associated with specific nutrient deficiencies

Taken from Bernard, et al. Nutritional and Metabolic Support of Hospitalized Patients. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1986.

Taken from Bernard, et al. Nutritional and Metabolic Support of Hospitalized Patients. WB Saunders, Philadelphia, 1986.

Unfortunately, most signs and symptoms identified through clinical evaluation are very nonspecific. And they can be attributed to more than one nutritional deficiency as well as non-nutritional factors. In order to further define the type and extent of nutritional deficiencies, adequate laboratory evidence must be obtained.

1 Eva Politzer Shronts, MSc, RD, CNSD. University of Minnesota, Minneapolis United States

* Article published in Lecturas sobre Nutrición 1997; 1(4); 40-55. RMNC 2011; 2(1): 59-72.